DecaTherm – Fossil-free thermal networks

While the IEA recommends promoting fossil-free peak load solutions for thermal networks, fossil-based peak load concepts continue to dominate in Switzerland. Without a change of course, this could result in up to 0.8 million tons of CO₂ per year by 2050. The "DecaTherm" project collects best practice examples and prepares them for more targeted communication and implementation of fossil-free solutions.

Fossil fuel and biomass-free is rarely tested

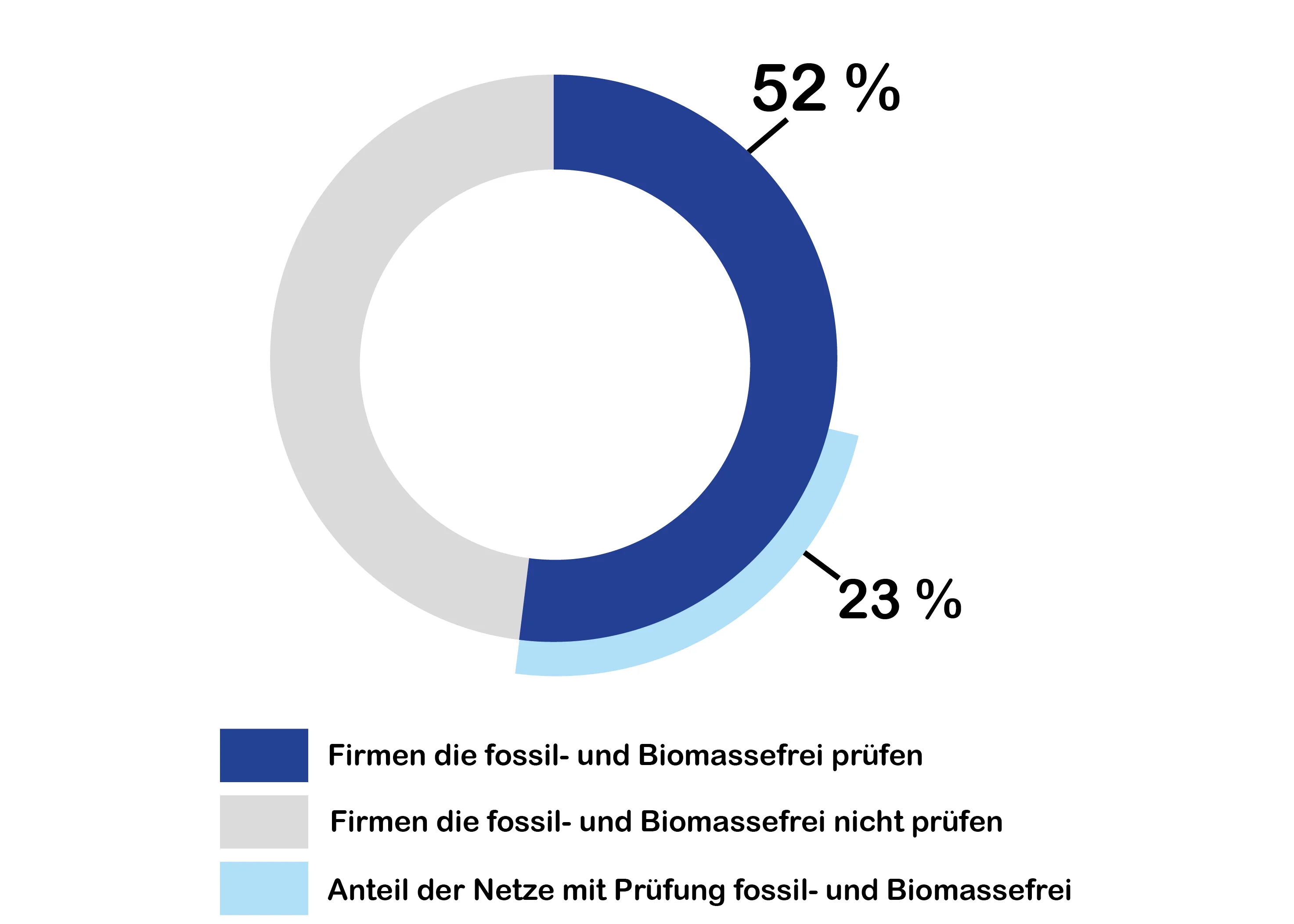

Currently, the implementation of a bivalent thermal network (renewable base load and fossil peak load) is the standard. However, a fossil fuel- and biomass-free variant is usually not considered. According to a survey conducted as part of this study, only just under half of all companies are conducting a feasibility study for a completely fossil fuel-free variant, and even then only for less than half of their thermal networks (see Figure 1). A fossil fuel-free variant is therefore only being considered in one in four projects.

Fossil fuel-free and biomass-free thermal networks in practice

There are already several thermal networks in Switzerland that operate entirely without fossil fuels or biomass. They are generally based on renewable heat sources with low temperatures, such as lake water or waste heat, and use heat pumps to generate the required flow temperature. We have compiled the following fact sheets with specific examples of practical implementation.

Cost-effectiveness as a killer argument

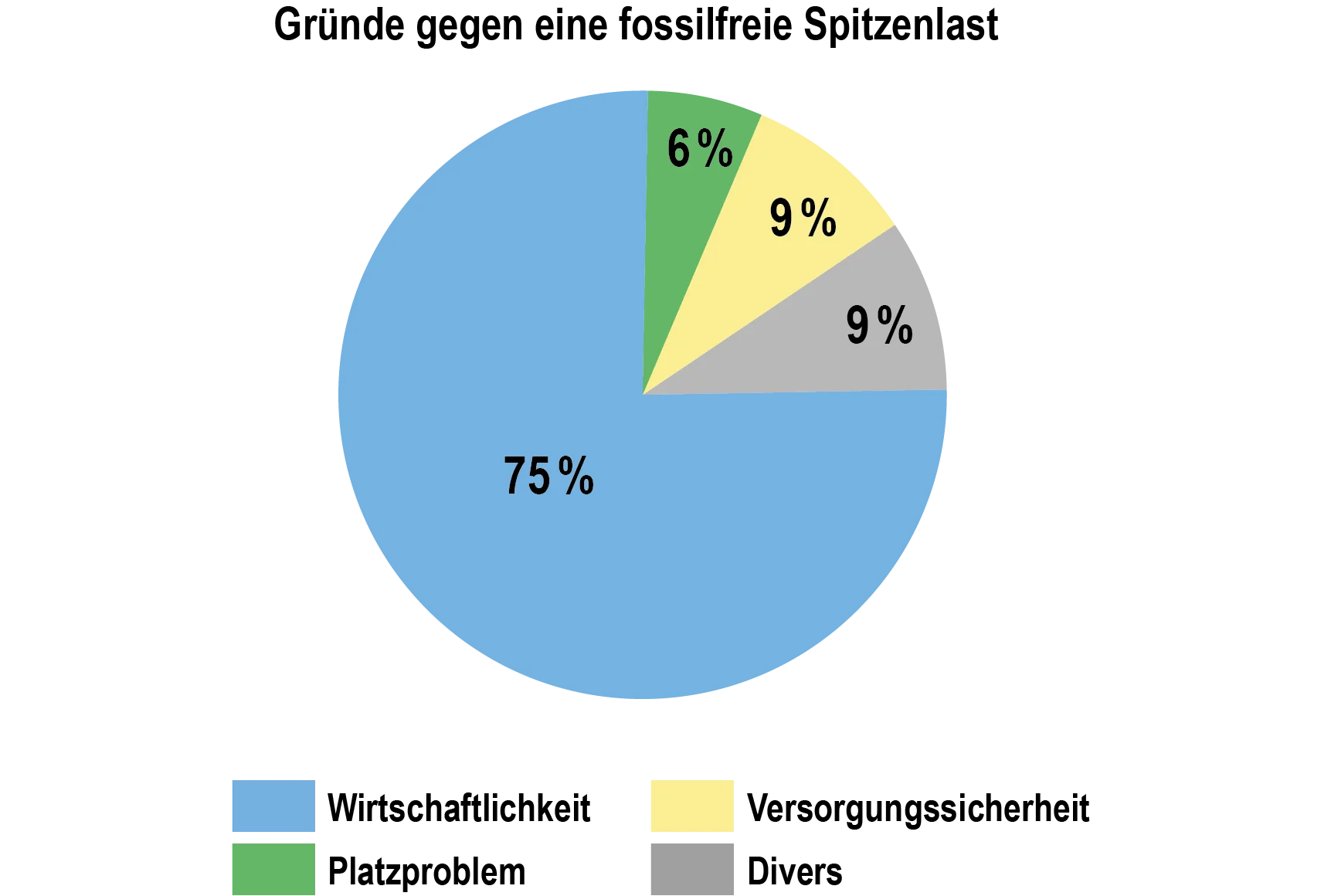

Completely fossil-free heating networks are technically feasible today. According to our industry survey, in 75% of cases, fossil-free peak load is not considered due to economic reasons – or it is not even examined in the first place. Figure 2 shows the reasons given for not covering peak load with fossil-free energy.

This overlooks the fact that there is no alternative to decarbonization. Of course, fossil-free variants often involve higher investments. However, the continued use of fossil fuels is not sustainable – neither in terms of climate policy nor in the long term economically.

Use of renewable heat sources and storage in fossil-free thermal networks

In the fossil-free networks examined, waste heat and seawater are predominantly used as heat sources. The flow temperatures are deliberately kept low in order to maximize the coefficient of performance of the heat pumps.

In central heat generation plants, flow temperatures of less than 60°C are sometimes achieved. Hot water is then produced either decentrally or by periodically charging local storage tanks with temporarily higher flow temperatures, for example once a day within a defined charging window.

In decentralized systems (anergy networks, cold district heating), only the environmental heat is transported to the customer, where it is brought to the required temperature by means of heat pumps.

Sensitive storage tanks are generally used in existing networks to cover short-term peak loads. When planning new networks, latent storage tanks with phase change materials are sometimes also considered in order to increase the energy density in the storage tank.

Life cycle cost comparison

The investment costs for fossil-free peak load coverage with heat pumps are higher than for a gas boiler, for example. However, the decisive factor is the total cost over the life cycle: with low electricity prices, the fossil-free option can actually be more cost-effective.

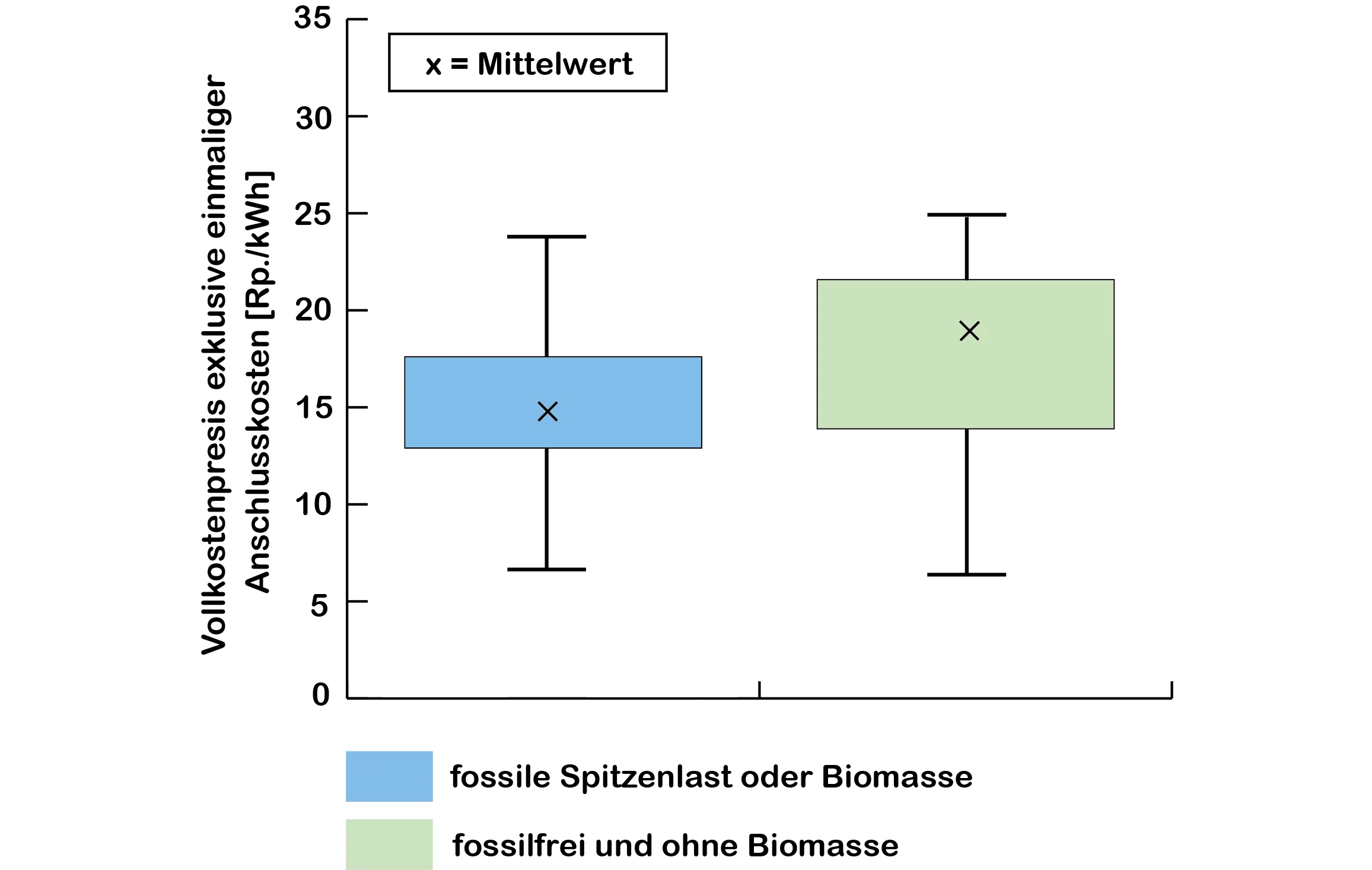

A full cost comparison (excluding one-time connection costs) shows that the prices of the fossil-free and biomass-free networks analyzed are on average only around 22% higher than those of a comparative sample of existing thermal networks in Switzerland, which predominantly rely on biomass or fossil peak loads (see Figure 3).

Cost reduction through reduction of peak load

The costs of fossil-free peak load supply can be reduced by reducing the frequency and intensity of peak loads. This increases the utilization of heat pumps and thus improves their economic efficiency. Possible approaches to this include the increased use of heat storage systems and operational optimizations in thermal network operation.

In urban areas, limited space poses a particular challenge: heat pumps require more space than gas boilers. However, the space required in the energy center can be reduced by decentralized storage solutions. In addition, redundancy can be outsourced—for example, through decentralized systems or mobile heating solutions that are available when needed.

Heat pumps are practically the only option

- Decarbonizing thermal networks with renewable heat sources and heat pumps is the most economically and ecologically sensible solution.

- Wood and biogas are only available in limited quantities and should be used primarily in sectors that are difficult to decarbonize and require high temperatures.

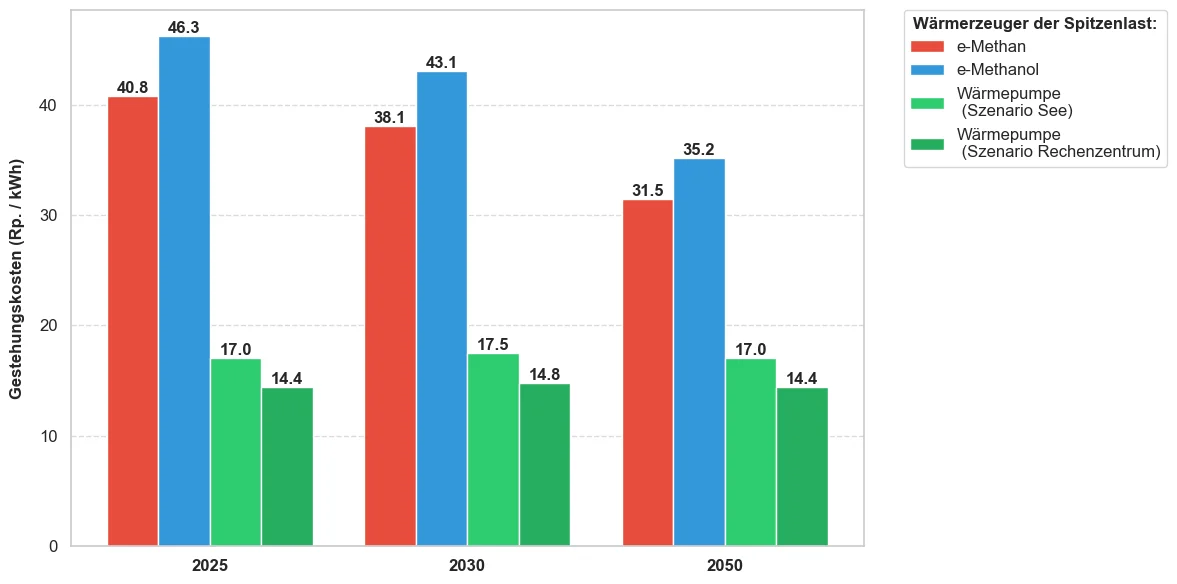

- Synthetic fuels are significantly more expensive: by 2050, e-methane is expected to be around ten times more expensive than fossil methane – and thus still more expensive than heat pump solutions.

Synthetic fuels: Expensive, scarce, and environmentally questionable

Based on expected technological developments, the heat production costs for fossil-free peak load coverage using various technologies were calculated for the years 2025, 2030, and 2050 (see Figure 4). In all cases, heat pumps are the most cost-effective option.

In addition, there are uncertainties regarding the expansion of the currently very low production capacities for synthetic fuels, as well as the risk of indirect emissions, for example from the Swiss electricity mix. Depending on the origin of the electricity, the greenhouse gas emissions from synthetic fuels can be almost as high as those from fossil methane.

Hoping that synthetic fuels will be the solution of the future is effectively equivalent to a “business as usual” strategy and therefore cannot be recommended.

CO₂ capture is too expensive and hardly realistic in decentralized plants.

Decarbonizing thermal networks through carbon capture and storage (CCS) is technically difficult to implement because the CO2 concentration in the exhaust gases is low and the quantities are irregular and locally limited. Capture would therefore only be realistic—if at all—indirectly via direct air capture (DAC). However, the costs involved are very high and future cost reductions are uncertain. In addition, there are major uncertainties regarding transport options and the availability and long-term stability of underground CO2 storage.

The current capacity of DAC is completely insufficient: in 2022, less than 10,000 tons of CO2 were captured worldwide using DAC – compared to the more than 400,000 tons of CO2 generated annually by the combustion of natural gas in Swiss heating networks alone. DAC can therefore only be considered as a last resort to compensate for residual emissions that are difficult to avoid – not as a substitute for a consistent switch to fossil-free heat sources.

Conclusion and recommendation

- A “business as usual” strategy with fossil fuel peak load coverage and the hope of decarbonizing it in the future through CO2-neutral fuels or CCS is strongly discouraged. This strategy is associated with great uncertainty and would most likely incur higher costs than an early switch to a fossil-free solution.

- Fossil fuel- and biomass-free peak load coverage is already technically feasible today, as numerous practical examples show. If a low-temperature heat source is used, there is also the option of cooling in summer - an advantage that is becoming increasingly important in view of climate change.

- New thermal networks should be consistently planned and implemented without greenhouse gas emissions.

- Existing networks should be specifically prepared for a fossil-free transition through technical, operational, and planning measures.

Related projects and links

- SWEET EDGE

- Utilization or permanent storage of CO2 from biogas plants

- Smart Energy

- Microgrids

- “District heating, but now without CO₂ emissions” an article in German by Benedikt Vogel in Renewable Energies (December 2025) (PDF 557 kB) or in French: “Le chauffage urbain, mais sans émissions de CO₂” (PDF 570 kB)