What is the difference between microgrids and smart grids?

Microgrids can operate independently of the power grid and increase security of supply in the event of grid disruptions. Unlike smart grids, which integrate smart technologies, microgrids can operate autonomously. They support the integration of renewable energies and prevent overloads by storing and consuming energy locally.

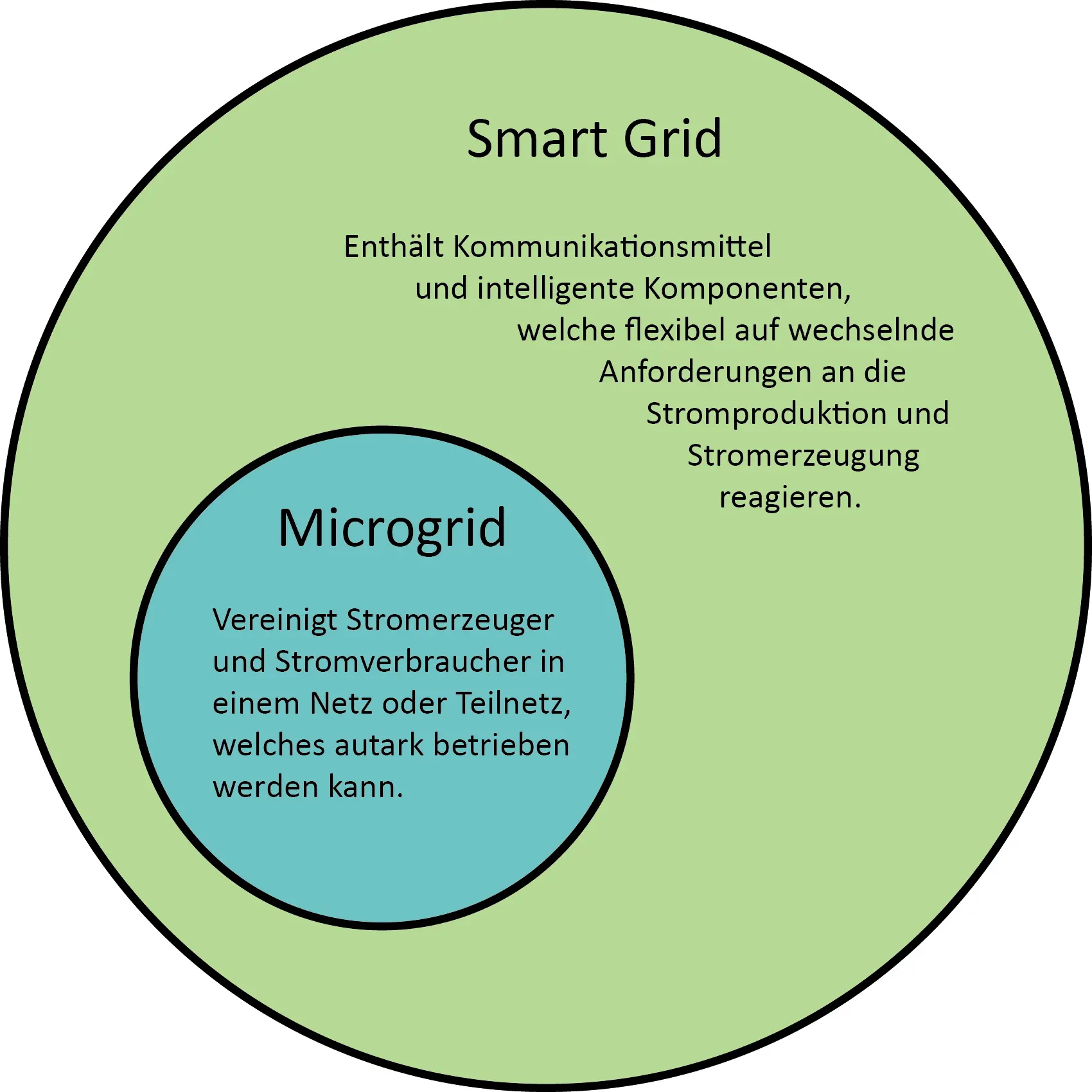

The terms microgrids and smart grids are often used interchangeably. Although a grid can be both a microgrid and a smart grid, the meanings are not entirely the same. The Venn diagram illustrates the relationship between the two. An electricity grid is a microgrid if it can be operated independently, i.e., as an isolated grid. In normal operation, it can still be part of the higher-level electricity grid.

Smart grids, on the other hand, are power grids that include communication infrastructure such as smart meters and "intelligent" components such as load management or dynamic production curtailment, but do not necessarily have to be able to operate independently.

Microgrids are therefore a subgroup of smart grids, even though the term smart grid is sometimes used to refer to subgrids that can be operated independently of the higher-level grid.

What can microgrids do that the normal grid cannot?

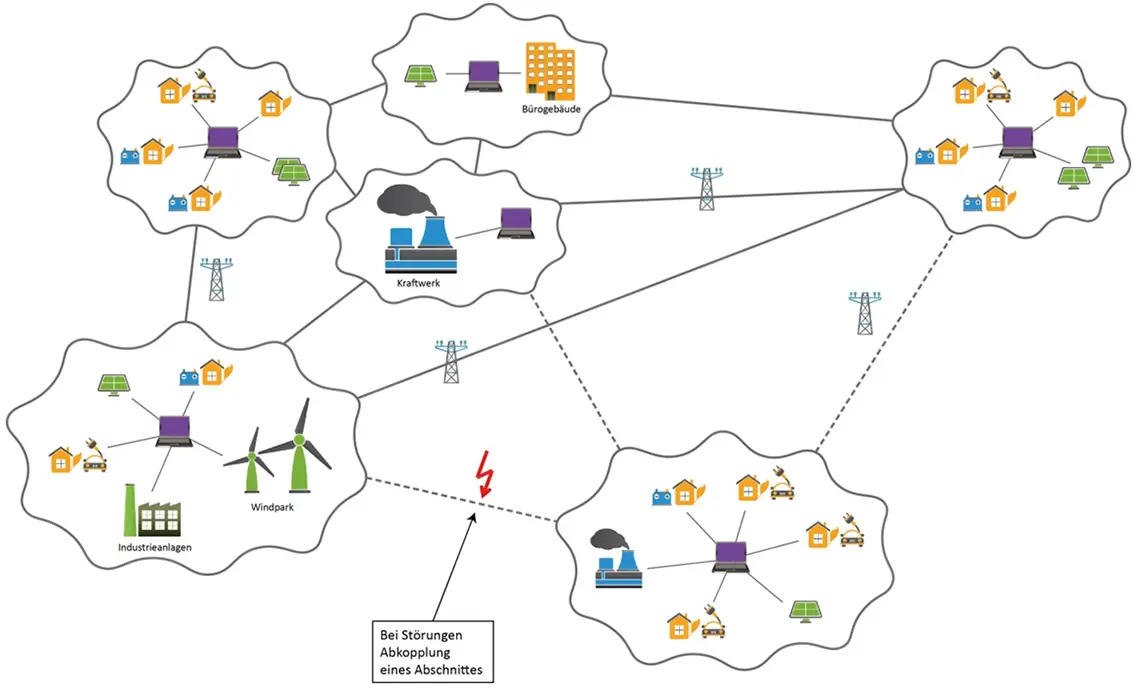

Since microgrids can operate autonomously in the event of grid problems, the load within a microgrid can be served independently of the higher-level power grid. In the event of a power outage, for example, a microgrid-enabled subgrid will switch to island mode. Since every microgrid also has integrated power generators, it can ensure the power supply within its own grid, shielded from external influences. This can be essential for critical infrastructure. Hospitals with intensive care units, police headquarters, and server farms are thus much better protected against potential outages.

If, in the future, more and more energy from renewable sources such as PV systems or wind turbines is fed into the grid, electricity production will be primarily dependent on weather conditions and can no longer be fully controlled. On particularly sunny or windy days, these systems will feed a particularly large amount of renewable energy into the grid. This could place a critical strain on the grid or, in extreme cases, even overload it. To prevent this, expensive grid upgrades would be necessary without microgrids or smart grids.

With the intelligent components of a smart grid, this overproduction can be predicted using weather forecasts, allowing for flexible consumption (demand side management, DMS), charging energy storage systems, or reducing the output of individual production plants (curtailment). These measures are often referred to as peak shaving.

Since microgrids connect electricity producers and consumers within a grid section, the excess electricity produced can be consumed locally or regionally, which prevents critical line loads in the transmission grid.

Very large-scale renewable energy production therefore benefits from microgrids, among other things because stochastic electricity feed-in can be well integrated and there is little or no need to expand the grid.