Pro-human AI Design explained

AI has the potential to manipulate what makes us human – e.g., our ability to form relationships. Prof. Stadelmann explores how to make sure the technology does not dehumanize us.

How can AI systems be designed to strengthen what makes us fully human, rather than undermining core aspects like relationality, responsibility and autonomy? “Pro-human AI tech design”, or “pro-human AI” in short, is the field of study concerned with these questions. But why is it necessary in the first place?

Recently, the New York Times published an article detailing how design choices at OpenAI to enhance user engagement with their product ChatGPT lead to nearly 50 cases of psychosis: After conversing with the chat bot, nine users needed hospitalization and three died. The underlying issue was that the dialogue system had been designed to please humans by appearing supportive and understanding, making it too agreeable; the former “hacked” human users’ natural drive to form relationships, and the latter supported, e.g., suicidal tendencies.

These tragic incidents serve as a prime example for the major AI risk of dependence, specifically of manipulating the human core: our fundamental properties that make us human and that we do not want to lose. Apparently, AI isn’t just changing work but is changing us as it interacts with us on a deep level (in the example above: by using human language and appealing to affections, triggering attachment). In related circumstances, social media scholars have developed the field of "pro-social tech design": principles and methods to analyze how a technological artefact interacts with society, measuring their impact, and designing for minimized negative influence.

Consider the “like” button as an example: Created as a harmless device to boost user engagement (mind the pattern!) by signaling support for posts, it has over the years changed our collective behavior as societies: the way we write to solicit likes; the way we strategically spend likes to boost agendas; etc. So much so that 15 years later we find society is split into neatly separated filter bubbles that can hardly stand talking to each other on major issues. Realizing the effect of the technology’s design on that outcome, the researchers have suggested “pro-social” design methods to overcome respective problems (oversimplified: by, e.g., adding a button “show me the common ground to my thinking”).

Seeing similar potential in the field of AI, an interdisciplinary team at CAI around Prof. Thilo Stadelmann, Prof. Christoph Heitz (AI fairness, ZHAW IDP), master’s student Rebekka von Wartburg, and external advisors from the humanities, together with the company AlpineAI AG as use case provider set out on a journey to (a) compile what makes up the human at their core; (b) measure how a given AI system for a specific use case interacts with these core property; (c) and develop interventions to the system’s design to mitigate any negative influence (if any).

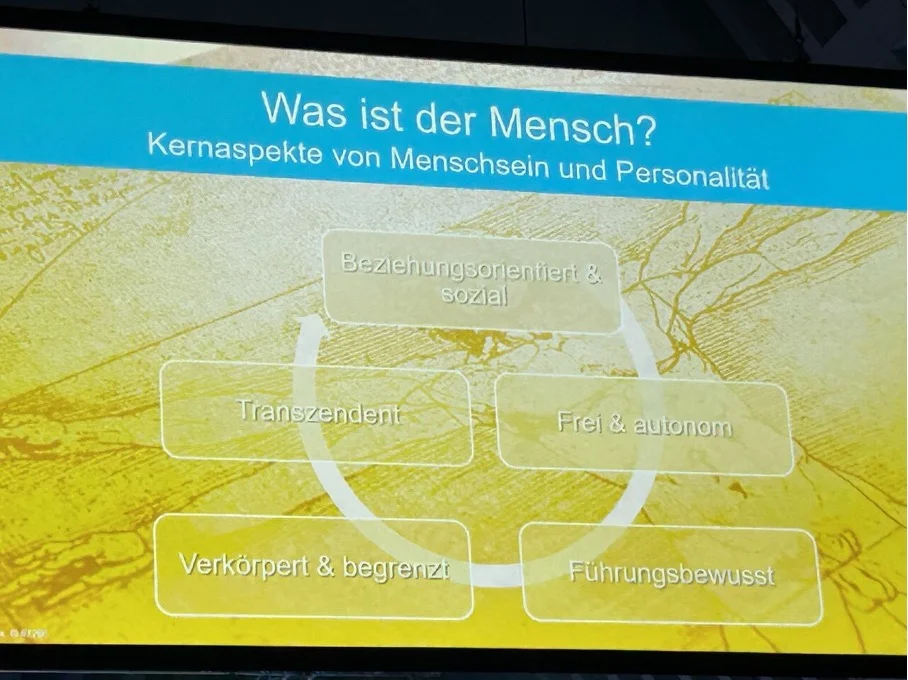

What makes up the human? This question is hard to answer once and for all, but after surveying the literature across psychology, anthropology, sociology, and theology, the following core properties appear sufficiently agreeable and complete: Humans are

- Relational and social: We cannot live in isolation, hence we seek connection to an other.

- Free and autonomous: We are fiercely independent; revoking a human’s right to have any say in their own affairs (i.e., slavery) has been rightly abolished.

- Driven to shape: Everyone rules about their own circle of influence, exhibiting a drive to shape their environment.

- Embodied and limited: Arguably, we are not especially fond of most of the limitations of our mind and body, but as Neill Lawrence points out in “The atomic human”, this is also what shapes our intelligence and humanity; becoming limitless hence is becoming less fully human, which is a qualitative regress.

- Transcendent: At the least, we all seek purpose and meaning.

Pro-human AI design is the habit of taking into account, when designing any specific AI system for a specific use case, how this systems interacts with each of these properties: Is any stakeholder’s competency to exhibit one or more of these traits diminished profoundly by the AI system (e.g., does work become meaningless? Is the user’s ability to form meaningful human relationships or act socially reduced? Would their feeling of agency be weakened, the free forming of opinion manipulated?)? Then, countermeasures can be considered alongside other factors of product design.

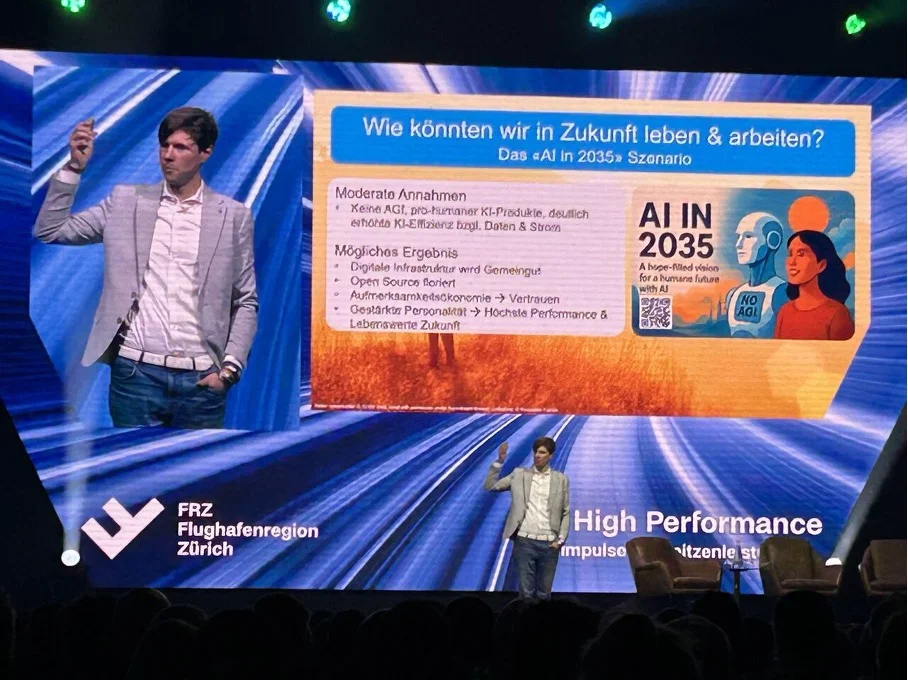

More than 1’500 business leaders have been introduced to preliminary results around this approach at various keynote speeches recently, e.g., at the Swiss Insurance Award 2025, the IPA Jahrestagung 2025, or the 25thFRZ Wirtschaftsforum 2025. Additionally, NZZ Jobs covered it in an interview, and the AI in 2035 scenario has been drafted based on the assumptions that AGI will not materialize within the next 10 years, but pro-human AI systems will, showing the huge potential of this approach especially for the European economy.

The team at CAI will continue research in this direction and are actively seeking collaborators from academia and industry. Please reach out if you are interested.