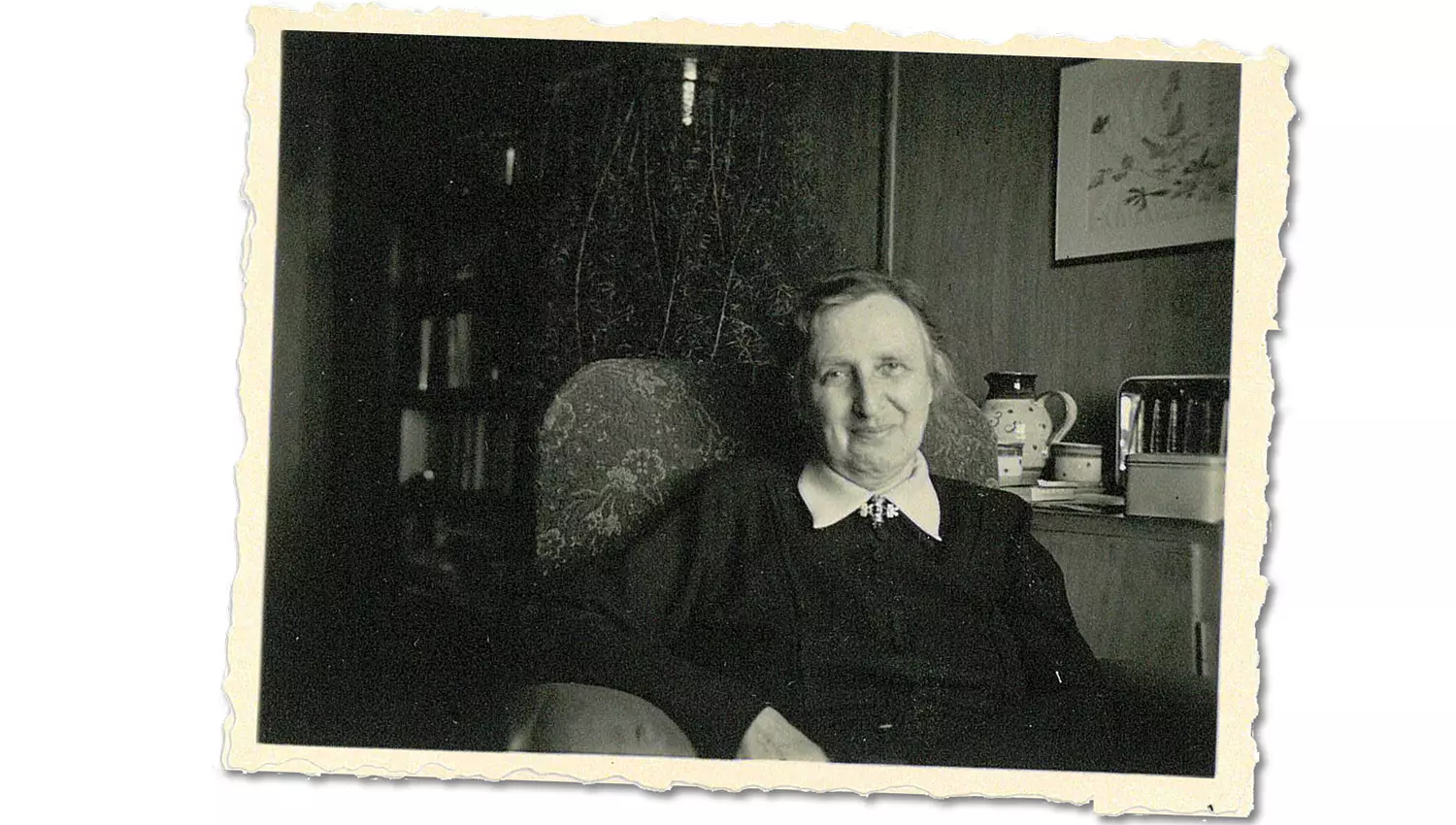

Dialogue instead of confrontation: Zurich social reformer Emmi Bloch

With a civic mindset and unwavering optimism, Emmi Bloch (1887–1978) fought for women’s suffrage and vocational training for social workers

The people were hungry. In June 1918, the final battles were being fought on the fronts, the Spanish flu had reached Europe, and almost 700,000 people in Switzerland were dependent on emergency assistance: one sixth of the population. In the city of Zurich, 4,000 children received a free breakfast every day. Meanwhile, the export and food industries were piling up the profits.

The social democrats took to the barricades. On 10 June, more than 1,000 women marched in the front of the City Hall, the meeting place of the Zurich Cantonal Council. ‘We are starving,’ their signs read. They were not let in, but they had brought demands, including the immediate requisition and fair distribution of all necessities and establishing a living wage.

The day before, Emmi Bloch appealed to the conscience of bourgeois wives and mothers in an article in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), urging them to renounce ‘sumptuous elegance’ and teach their children the ‘simple way of life’. Why, while the demonstrators were calling for bread and wages, was the co-founder and first secretary of the Zurich Women’s Centre trying to elicit a sense of responsibility from rich citizens?

Fierce women, indifferent councillors

It was not enough. On behalf of the Executive Board of the Women’s Centre, Emmi Bloch finally called upon the government to review the demands of the demonstrators and listen to them. In addition, she asked that the Cantonal Council survey the extent of malnutrition and expand the rationing system.

After another solidarity rally a few days later, this time with 15,000 people, the women of Zurich submitted a popular petition for the first time on 17 June. Bloch, who was not one of the demonstrators, was present at the meeting and wrote in her diary that evening: “Insanely heightened ferocity on the one hand, criminal indifference on the other. They [the bourgeoisie], like many of our women, are caught up with their own concerns and cannot see their way to believe in the plight of others.”

Founding of a professional association for social workers

Emmi Bloch was no street fighter, but as a trained social worker she knew what life was like in the streets and in the workers’ housing. She was not a socialist, but she read socialist writings and agreed with August Bebel and Lily Braun on the women’s question. She was not a suffragette, but as a publicist, functionary, speaker and lecturer, she fought for women’s suffrage and for the vocational education of women all her life.

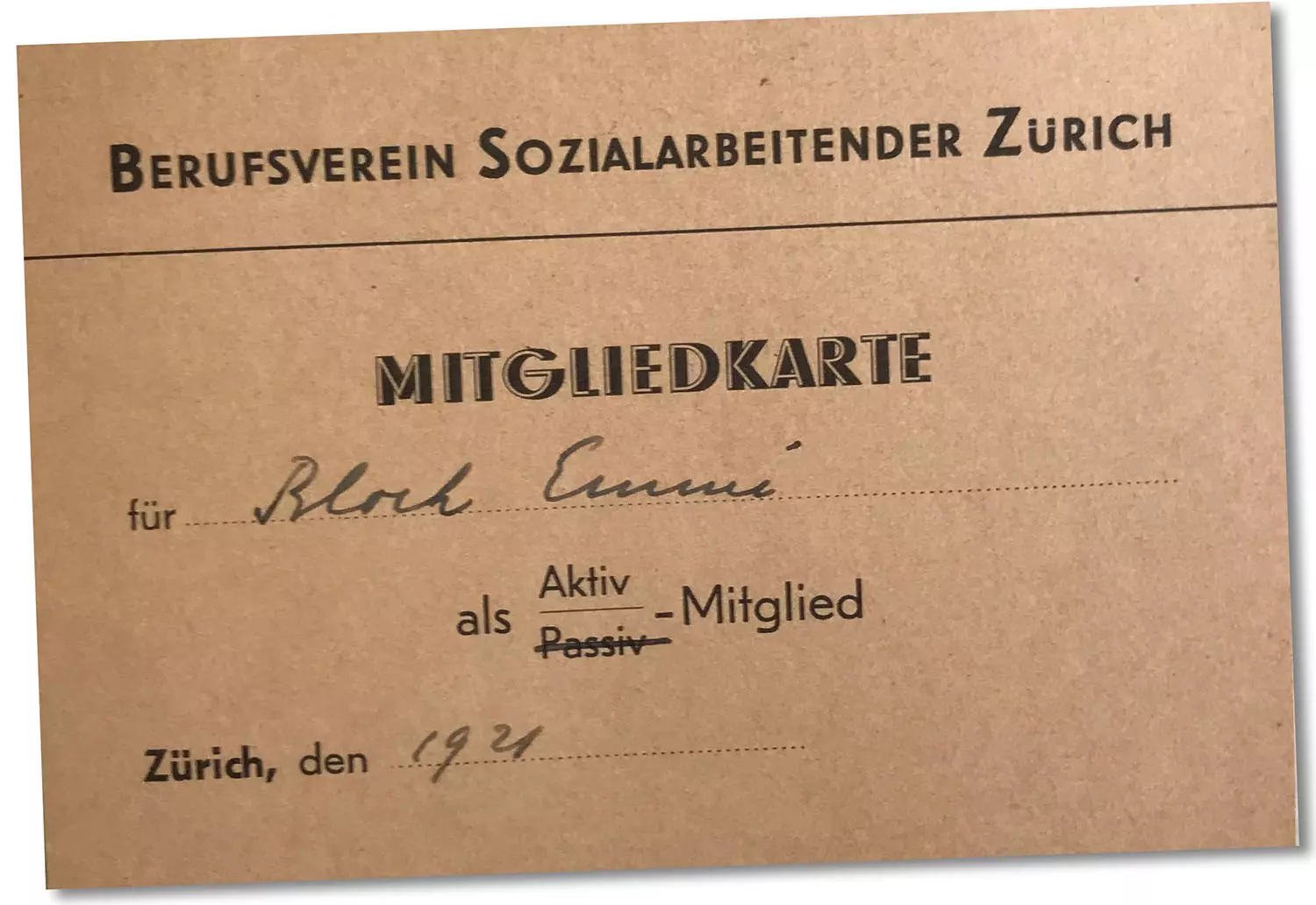

She never joined a party, but she was well aware of the political power of organisations and founded several of her own. Examples included the Zurich Association of Social Workers – the first of its kind in Switzerland – in 1921, and the Swiss Central Office for Women’s Professions (Schweizerische Zentralstelle für Frauenberufe) in 1923, making her Zurich’s first careers counsellor for girls and women. In addition, the Working Group on Women and Democracy was founded in 1933 as a reaction to the seizure of power by the National Socialists in Germany.

Away with the corset

Bloch was born in Zurich in 1887, the middle of three daughters. The family had a linen factory in the industrial quarter and ran a middle-class household with a cook and maid. Their home was appointed with Biedermeier furniture, and a big old grand piano where the family would play music and sing together. Although the Blochs mainly associated with the Jewish community, and their mother presided over the Jewish Women’s Association, they were progressive-liberal in outlook. Emmi Bloch, who was very devout throughout her life, rejected dogmatic confessional ideas, instead believing herself to be in pure communion with God, as she experienced in the writings of Rilke.

Her family nicknamed her Owl Sister because she was so well read. On her death in 1978, she left behind over 2,000 books. As a child, she would sometimes lock herself in the toilet to read. The Wandervogel youth movement, which was very popular in bourgeois circles at that time, marked a mild but vital escape from ‘superfluous convention in fashion and more important things’. These young people would go on excursions, cook for themselves and write poems. After her first Wandervogel trip, Emmi Bloch cast off her corset forever.

An introduction to women’s work

All three sisters had to work in their father’s laundry for a certain period of time. After attending the trade section at the girls’ school and training as a seamstress, Emmi Bloch worked in a hosiery mill for three years. There she would send out clothing to be worked on at home and take back the sewn items. This brought her into daily contact with workers, whom she would visit at their homes when they were sick.

She witnessed the economic hardship of such families. The desire for meaningful social activity led her to enrol on the Introductory Course on Women’s Work’ in 1910, which had been initiated by Mentona Moser and Maria Fierz in 1908. The course gave rise to the Social Women’s School in 1920, today the Department of Social Work at the ZHAW.

‘Rational activity’ for women

Welfare courses marked the first opportunity for women in Switzerland to train in social work. Those attending such courses – mainly the daughters of wealthy families – would receive a ‘social education’ designed for women. The aim was to enable them to remedy social injustice, albeit free of charge. At first, it was not about professions per se, but about the ‘concept of social action’ as a ‘rational activity’ for women, as Fierz writes in 1912 in the yearbook of the Swiss Society for School Healthcare.

Once the Civil Code was introduced that same year, the state had more obligations in child and youth welfare than was the case with the cantonal laws. Official guardianship and the Municipal Child Welfare Office had also been established relatively recently in Zurich. Trained staff were increasingly in demand, especially in inpatient facilities.

Liberation from ‘parasitic’ married life

Emmi Bloch, however, was drawn to care outside the home. She completed the course and internships with top grades and then went on to work at a tuberculosis care centre, both in the office and in the field. She would make house calls – up to 1,200 a year – and help with the medical consultations, deal with correspondence and manage files. Her annual salary was 2,000 Swiss francs. Bloch was one of the first social workers in Switzerland to be paid.

In 1916, she took up a leadership role at the Zurich Women’s Centre, the umbrella organisation of 14 women’s associations. In that capacity, she arranged employment opportunities for women, informed them of support services such as spa stays, and coordinated such programmes. There are also rooms where people could warm up and get things mended, plus a rent office to support tenants who had become insolvent.

With the push towards professionalisation, public recognition of social work grew. Women appeared before committees and were invited to political conferences. Bloch used such appearances to promote vocational training for women. As far as she was concerned, getting women professionally active was a social mandate, a ‘vocation to contribute to the great achievements that are necessary for the whole of society to live,’ in her words. Furthermore, she saw this as emancipatory empowerment, a way of breaking free from domestic violence and a ‘parasitic life without honour or authenticity’.

For women’s suffrage

Bloch was a member of the Zurich Voting Rights Association, and publicly campaigned for women’s suffrage from 1917. Her articles were published mainly in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, the National-Zeitung and, of course, the Schweizer Frauenblatt, of which she was editor-in-chief between 1933 and 1943. In addition, she taught the subject of women’s issues for almost three decades at institutions including at the Social Women’s School and the Adult Education Centre.

Welfare work showed social reformers the necessity of voting rights as a means of work, as the allocation of funding and permits were being discussed in meetings without women being present and able to give information about the purpose of the money. Yet she was optimistic. In 1919 she wrote, ‘The time for women’s suffrage has come. Switzerland will not be able to close its mind to it.’ Swiss men would see things differently for another 52 years.

In poor health

For all her commitment, Bloch was a typical representative of the bourgeois women’s movement: she was not looking to confront, but rather to mediate. She cemented the double burden so familiar to women by advocating for women to be active both in the domestic sphere and in gainful employment. She even received criticism from men, who questioned how this could possibly be done. She had no answer to this, or rather responded indirectly with her own example: total dedication to her vocation.

Such devotion fulfilled her, but it also exhausted her strength. Even as a young woman, she often suffered from health problems, bronchial catarrh, angina and overexertion. She had to take frequent breaks and go on spa cures. During a Wandervogel excursion in 1916 in the Valais, she injured herself and went into shock. There was no lasting physical damage, but she may have incurred psychological trauma, as from then on she increasingly suffered from claustrophobia. In addition, she was an ongoing target of anti-Semitic hostility.

A cosmic task for motherhood

Emmi Bloch sought to transform women’s maternal potential into political power. As such, she promoted professions that she believed to be associated with motherhood, i.e. not trade professions. She understood domestic chores and ‘the cosmic task of motherhood’ as ‘women’s allotted work’.

Yet Bloch herself experienced motherhood merely as a ‘spiritual and mental state’: she remained unmarried and did not have any children. She lived with her parents until the age of 42, then took a flat with her friend, the social worker and career counsellor Anna Mürset. In 1944, after her early retirement, she moved into a house in Uerikon on Lake Zurich and lived there with a maid until her death in 1978.

Bloch cultivated many close friendships with both men and women. Why did she never end up having a proper relationship or getting married? We just don’t know. She always kept her private and professional lives separate and requested that all of her diaries be burned after her death. With one exception, Emmi Bloch’s nephew and executor complied with her wish.